Cheryl texted me her STAAR results. We’d been talking about the previous post.

Cheryl: English I - 66% Approaches, 50% Meets, 12% Masters

English II - 70% Approaches, 57% Meets, 11% Masters

Our. Kids. KILLED. It!!!! I believe for English I students (before retests and including retested students in

the spring it was 79% Approaches, 62% Meets, 12% Masters. Only my kids, no re-testers:

82% Approaches, 64% Meets, 14% Masters. And I don’t know the final tally with re-testers that may

have passed. 2021 was my first administration at this campus since we didn’t admin in 2020.

Shona - So this means…

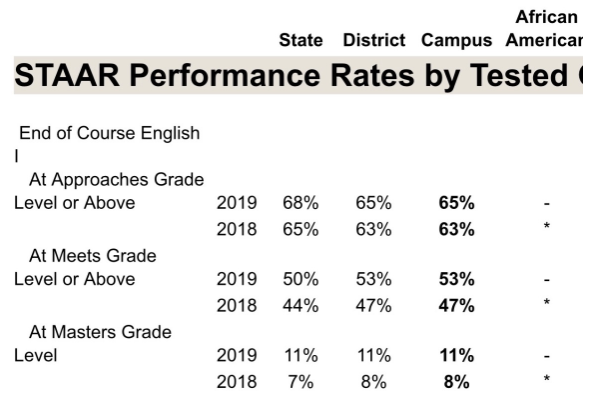

Before Cheryl’s Strategies | Cheryl’s Class | Change |

2019 Approaches State 68%

District 65% Campus 65%

2019 Meets State 50%

District 53% Campus 53%

2019 Masters State 11%

District 11% Campus 11% | 2021 Approaches State 66% District Cheryl’s Class 82%

2021 Meets State 50% District Cheryl’s Class 64%

2021 Masters State 12% District Cheryl’s Class 14% |

20% gain

14% gain

2% gain |

Shona: Holy cow, Cheryl! What did you do during COVID to get such results?

I know that I always rely on you to further the prototypes that we design based on the needs

we are seeing. But I didn’t expect such a gain the first year.

Cheryl: That’s a great question. This year was really the culmination of things I’ve learned over the last

5 years (mostly from you!) that I was finally able to put into practice all at once.

Some foundational things I think are a starting point for this conversation:

Understanding the new TEKS helped me understand the depth at which our students needed to understand texts. And the types of texts they needed to read--and how they should be constantly making connections within and across texts of various genres. Even though we changed topics many times in the class, students often commented that our class seemed like one giant thematic yarn ball--and I think any good reader/ writer probably feels the same way about everything they read and write. That was a sign I was on the right path.

Reading/ Writing/ Speaking/ Listening/ Thinking as a constant cycle in our class. We were always doing all 5 around a text, around our own writing, around sharing, around talking as a starting place for all of the above.

These two pieces became the foundation for everything else. I think some people reading this probably

want to know what textbook we used or what workshop I went to that made me successful in 6 hours

or less, but this is a culture we have to create in our classes, and it’s not easy. We (usually) have to

fight trends in instruction that may not have encouraged real thinking and fight the idea that there is

some sort of “formula” to the right answer or the best essay. It’s an organic process.

And if a teacher isn’t committed to that type of paradigm shift (s)he won’t be successful.

Shona: Wow. That’s a lot to unpack. I have always felt that you absorb things over time and then put

them back together in a way that works for your teaching style and the kids in front of you that year.

I see that the two major things you mention are about your understanding of the TEKS and your use of

the domains of literacy. A third might be missed - the paradigm shift you experienced to a more

constructivist approach to instruction in cognitive literacy processes as opposed to a text based

approach that is in our instructional historical dna. LOL.

Cheryl: Yes, I think what you mention is a huge key. It took me a long while to realize this,

but it doesn’t matter WHAT we read, it matters what we do with what we read.

Please know that of course it matters what we read, but too many people are focused on teaching texts

and not focused at all on how to connect them or what to do with them. Of course I had a plan,

I had things I wanted my students to read for certain reasons or to connect in certain ways,

but some of my plans happened, and some of them didn’t. Sometimes I would scrap something

so we could spend more time on another thing or so we could add in something related to what

they wanted to know more about. We can talk about “student centered classrooms” all day long,

but unless we are ready to follow their lead in interests, pacing, and unpacking, we aren’t going to

see them engage to the level of depth required in these new standards. AGAIN: Of course I had texts

and tasks planned, and NO, they didn’t always like it (at first), but as we built a culture and classroom

together, we could move some things more into their lane.

Shona: So, really, I’m curious about what you taught about diffusing the passages that matched this

organic view of instruction and still caused gains for the students. I know you were using the fact tracker...but how did you roll it out, adapt it. What sense of it did the kids take on? How did their take change the process as you taught it?

Cheryl: I start the year with a philosophy that has really helped me understand texts more deeply and we roll

out baby steps. I don’t get to the full fact tracker until the 2nd semester because in the first semester,

our focus is on developing the new paradigm.

In the first two weeks of the semester, I introduce 2 concepts:

As we look at everything being an argument, I introduce the main elements of argument and we look for those in various genres. We quickly boil this down to “what’s the point?” or “what are they getting at?” --in genres like poetry, drama, fiction, etc. this often presents as one or more themes. Although it takes them a while to get good at it, I’ve taught them probably the most difficult skill we’ll work on all year and a process to identify it from Day 1.

Shona: This makes a lot of sense to me. Some of the questions I use with this part are: What’s it about? Why does it matter? Or when I’m feeling snarky, I ask: who cares?

Cheryl: When we get to Story, we look at the elements of a story: Characters, setting, conflict, plot, resolution.

We start with basically a 5th-8th grade review of things they should have learned along the way

(this builds confidence) (and it only takes about 1 class period), then I give them a text set that

includes various genres. (Song, poetry, drama, news, short story, etc.) and have them work with a

partner or group to tell whether each is a story and why/ or why not. (They are all stories.)

Shona: Aw, I see what you are doing here. Nice.

Cheryl: (Not every poem is a story, but the ones I include, are). As a class, we go through the works

and identify the elements of story in each one and at the end of each piece we ask ourselves two

questions that we will carry through the entire year:

What happened? (plot, or your quick clue this isn’t a story)

What’s the point? (theme, claim, main idea THERE IS ALWAYS AT LEAST ONE POINT).

This hits on our TEKS in a million ways, but one of the best ways is that this is a self-monitoring tool.

If a student can’t answer these two questions, they need to re-read and try again.

Shona: YES. We use summarization and theme finding as a tool to monitor our comprehension

instead of a product to be evaluated. Changes how they use the strategy to become assessment

capable and aware of their own cognition/comprehension. That’s why Learning on Display focuses on

reasoning THROUGH reading and writing. Reading and Writing are the tools for our thoughts and

response to ideas.

Cheryl: Note here, that their answers don’t have to be correct here. In fact, at first, they are usually wildly wrong.

After we read a text and answer these questions, I ALWAYS have them stop and pair/ share.

This allows them to correct or confirm their ideas (OMG, LOOK→ another TEKS!)

Shona: I’m impressed with this allowance to be wrong. Too often we are the ones that identify that for kids.

Let’s let them marinate in error and wade out of it through their reading and writing reasoning processes.

Until we are comfortable with allowing them to identify their own errors, we are doing the thinking work for

them when we tell them that they are wrong. And we steal the joy of discovering what is correct.

Cheryl: You are absolutely right. But this, too, can be a huge struggle to build into the course, culturally.

My students have often been conditioned to believe they MUST have the right answer and at first find

themselves too paralyzed to provide any response at all or completely obsessed with being right--

which prevents them from learning at all. Believe it or not, at least initially, I generally have the best

progress and growth with my lowest level students. They are usually so fed up with school at all that

they are the most willing to throw anything out there. My honors students are usually most frustrated

with this process.

Shona: YAAAAS. It was HARD to sit by Micah and agree with all his incorrect reasoning.

But it was a critical moment for HIM. I took a stance as a collaborator and thought-partner

with him instead of the corrector. This allowed me to ask...wait a minute...

I thought we proved all those wrong! Why isn’t D correct? This stance preserved his dignity,

but also didn’t stop his thinking. He was the one that ultimately decided how to revise his thinking

and reject what he initially thought was right.

Cheryl: Yes. My students have to learn early on not to mark any answer I agree with! Haha!

I’ll agree with whatever they say, no matter what! They have to be bold enough to think it out and

question each other’s thoughts.

Shona: I found that in my research as well. They have to be willing to reject the teacher’s ideas and go

forward with their own ideas and reasoning processes. It’s our job to allow it.

Cheryl: And model it. I do a lot of modeling and thinking aloud. I also sometimes have to have a

conversation with my classes (for the benefit of my students who are quick to answer everything).

This is about the process. Yes, the answer matters, but how we get to the answer matters most.

Shona: I had to go back and bold that statement.

Cheryl: And while some people have these internal conversations and debates in their heads in a

matter of seconds-- many, if not most, of my students need to hear these conversations so they can

develop these models for themselves. And, truly, this takes time. It’s a repetitive process that we

build into EVERY text we read. As the process becomes quicker and I can see my students are getting it,

I’ll layer in the next steps to build depth.

Shona: Agreed. That’s why I felt like I needed to model the convo in the previous blog post.

I don’t think the TEKS really are specific in how we reject answers we originally thought were right.

That stuff still needs to be taught - the thinking of how to make an inference and self-monitor to make

sure it’s right. The questions on STAAR really are aligned to TEKS, but I’m not sure we are really

teaching the implied THINKING TEKS that allow us to show mastery of the individual TEKS.

It’s like a hidden curriculum that really exposes the rigor more than anything I have seen out there.

We need to do more thinking about HOW we THINK.

Cheryl: That leads into how I layer depth\ into our reading and writing. We have to teach our students how

to think about the texts. From here we rebuild their ideas of annotation. Most of my freshmen come

to be thinking they have to summarize every paragraph… but annotation is a lot more than that.

And we don’t always annotate everything. It’s a tool to help our thinking.

We use the summarization annotation to paraphrase or summarize difficult (usually non-fiction) texts.

Sometimes our annotations are questions (because good readers ask questions!)

Sometimes we write or label what we notice, we write our understanding, make predictions,

make notes of our confusion to bring to the discussion later.

Shona: Once that annotation and internal talk become automatic, I let my kids let go of the annotations and

trackers until they need them for a point of struggle.

Cheryl: Answering our two questions (WH, WTP?) and using annotations as a tool are the first ways

I build writing into the course. We read, and as we read, we cycle through these small writings about

our texts.

Bonus Lesson Plans Cheryl and Shona Suggest: Using tools like the C3WP from the National Writing Project, we also learn to effectively identify and use

text evidence. https://sites.google.com/nwp.org/c3wp/home

Cheryl: I also love to teach Gretchen Bernabei’s kernel essays and tie some of the “Text Structures From the Masters” into our units. This really helps the students see text structure

and tie it to purpose. (Not PIE--haha, another soapbox I’ve picked up from you!)

Shona: Yeah - don’t get me started on PIE. I think we’ve given folks enough to think about today.

And you need to go fold the laundry and I need to go cook supper. :)

Cheryl: Thank you for this. I absolutely enjoyed it. If you are reading this and don’t already know,

Shona is THE BEST. <3

Shona: We are the best when we are thinking together. Love ya.