Costa and Kallick (1995) favor a model of feedback spirals over Argyris and Schon’s (1978) feedback loop. Conceptualizing feedback as a loop is problematic because a loop is closed. This implies that students are the same place at the conclusion of their learning as when they began. Improvement, Costa and Kallick (1995) insist, must be continual process. Spirals indicate a more recursive and continued progression of learning. Furthermore, feedback spirals can be used as decision making protocols for “the professional teacher who continually improves instructional practices in the classroom” (Costa & Kallick, 1995, p ?). Feedback Spirals also match Hattie and Timperley’s (2007) conception that feedback must “feed-forward.”. Fisher and Frey (2009) go even further, stating that feed-forward cannot be neglected because it it the very element that helps teachers respond to student learning and plan new lessons.

In the model below, I describe how feedback spirals will be woven into the research design and conversation between teachers and students about their writing. Using the spiral model fits the research design because the research questions are about how a high school teacher uses feedback from students to improve his or her approach to giving feedback that improves the quality of student writing. Using the spiral model to lay out the steps in the study mirrors the decision making protocols recommended by Costa and Kallick (1995). The spiral design also allows the teacher to respond to student attempts and plan lessons to continually address improvement.

Since the study is about how the teacher learns from the feedback continuum with writers, it might be confusing since the teacher is also giving feedback to students. In the model below, I lay out the research design in the spiral and then follow with a description of specific places where the research will focus on the teacher’s learning and use of feedback and not on the student learning. The teacher will evaluate the improvement of student response to her feedback, but the focus of this study is on the teacher’s perceptions and not on the student perceptions.

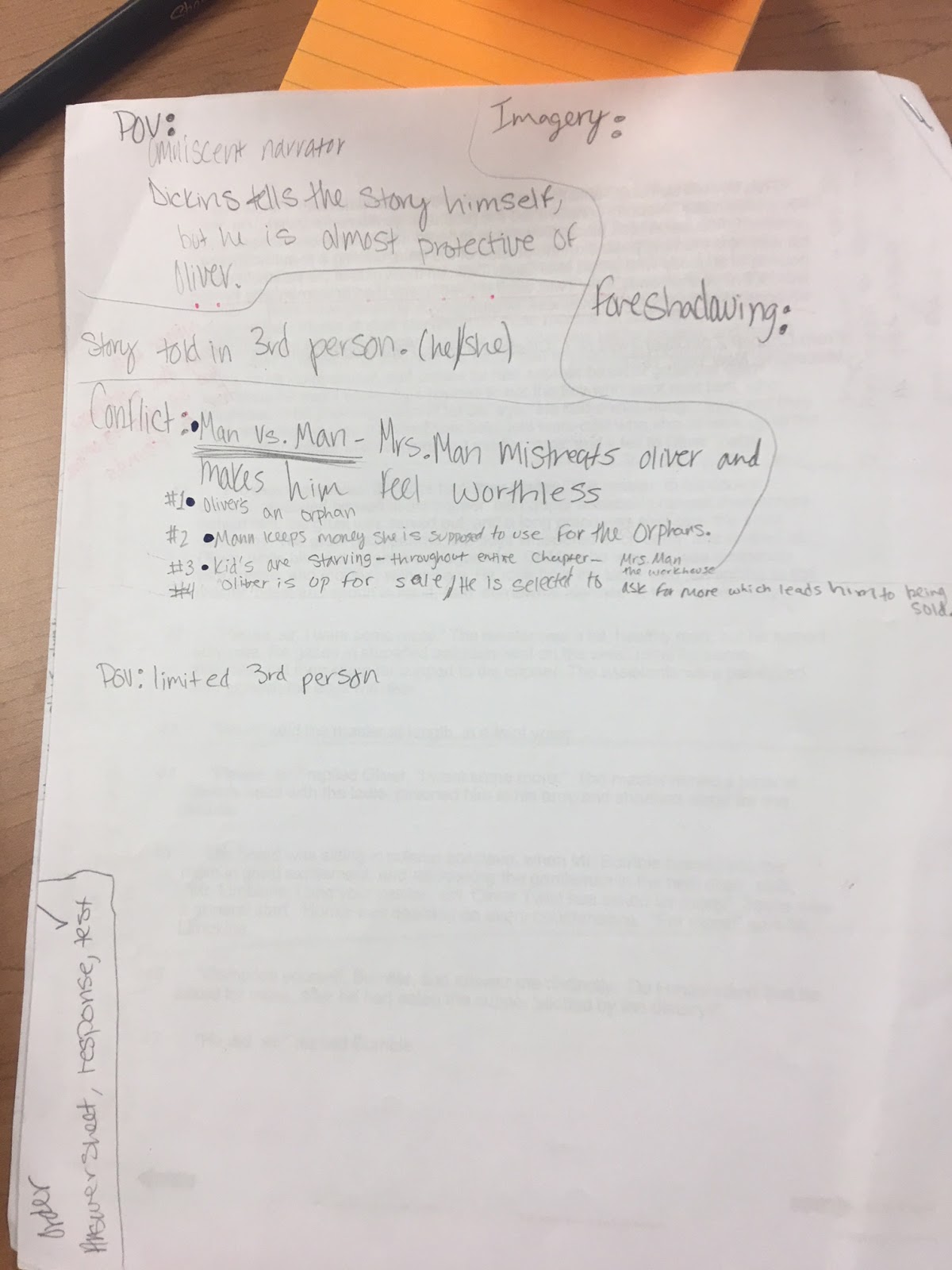

The feedback spiral begins at the bottom of the chart with the student composition. This study focuses on the teacher’s selection, use, and evaluation of feedback given to students about their writing. I’d like to highlight specific places in the feedback spiral where the study will have the greatest opportunity to reveal the teacher’s perceptions. In step 2, the teacher will read the student’s paper aloud as reader. This will allow the teacher to show how he or she is thinking to comprehend the text and digest the ideas. The think aloud will help the student writer see where the reader struggles to make meaning and how their text impacts the reader.

In steps three and four, the student will respond to the teacher’s reading of the text to clarify his/her intentions, ideas, and approach to writing. This discussion will be a primary place for the teacher to gather information about what the student was thinking and how he/she went about composing.

In step five, the teacher will use the feedback tool developed for the study to select the appropriate level of feedback to give to the student (surface/deep) and the type of feedback (task, process, self-extending) most appropriate for the student and the current writing performance. The teacher will think aloud to describe the choices he/she is making to select the feedback. The recordings and transcriptions will be useful to describe how the teacher uses the data in the previous steps to make a decision about what will be most helpful to the writer.

In steps 6-8, the teacher will deliver the feedback, check for understanding, and clarify if necessary. Before the student leaves the writing conference, the teacher will already begin to evaluate the effectiveness of her feedback. By recording and transcribing the exchange and collecting the artifacts, the teacher will be able to return to his or her decisions to evaluate how the student applies the feedback, collects evidence, and shares progress with the teacher in steps 9 and 10.

In steps 11-16, the teacher helps the writer set goals for the next writing performance and then evaluates how the feedback used in the first writing transfers to the next writing performance. This information can be helpful in learning what kind of feedback works best for particular students, writing situations/genres, etc. The teacher grows in the feedback loop by learning more effective ways to give feedback or searching for solutions to help students become better writers. When the writer grows because of what the teacher did, the teacher can identify his or her own effective practices for future feedback in writing conferences and receive guidance about restructuring lessons for initial instruction or whole class reteaching. Steps 17-19 extend the spiral to more and more sophisticated forms of teaching expertise.

Argyris, C., and Schon, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. New York, NY: Addison Wesley.

Fisher, D. and Frey, N. (2009). Feed up, back, forward. Educational Leadership. 67(3). 20-25.

Murray, D. (1982). Teaching the other self: The writer’s first reader. College Composition and Communication 33(2), 140-147.

Sacks, O. (1989). Seeing voices: A journey into the world of the deaf. Berkley, CA: University of California Press.

Vygotsky, L. (1986). Thought and language. A. Kozulin (Ed). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wilson, M. (2018). Reimagining writing assessment: From scales to stories. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.