The Lesson:

I observed a

lesson where the teacher was showing a video to activate background knowledge

for a passage they were about to read about Frederick Douglass. She modeled how

to collect information about the topic and to notice when the information

differed from her knowledge. Throughout the lesson, she carefully addressed

context, word origins, figurative language, inferences, historical references

and timelines. Her questioning was classic sequence of chaining: breaking the

tasks into small parts that the students could easily digest and gradually get

each question correct each question logically leading the student to the final conclusion

and interpretation. Masterfully done.

The Bouncer

As we

debriefed the lesson, she bemoaned how difficult it was for students to

remember the lessons and engage in the critical thinking. We talked about the

culprit – technology and instant gratification. While it is true that

technology influences the problems we see in classrooms, that’s not what’s causing

the problem.

First of

all, people these days have what’ I’d call an overdeveloped hippocampus. That’s

the part of your brain that’s the bouncer at a popular club. The hippocampus

decides what gets in and what stays out. If the information is novel, funny,

interesting, emotionally charged, or obviously relevant and useful, it gets the

hand-stamp and moves into short-term memory and has a chance at getting to the

dance floor of long-term memory and use.

If it’s boring, something you can

google, or not immediately useful and relevant, it goes home alone. No getting

in line for short-term memory. No chance of putting it’s moves on display in

the long-term memory dance floor. They might remember the time they were in

line, but they don’t remember much else. People are storing these memories like

bookmarks. They remember where they were and where they could go to find the information

if they want to, but they don’t actually encode the data as memories.

Y’all, that

means the memory is not physically or chemically or electrically encoded in the

brain. It’s. Not. There. Tell me that you don’t

have kids that have NO recall or memories of something you have taught. Tell me

that your kids are capitalizing i. Tell me that your kids go, “ooohhhh” when

you remind them of an activity you did or a story plot and can remember what

lesson they were supposed to learn from it. You can “cue” their internal

bookmark, but they don’t actually remember the lesson. Their hippocampus is a

very restrictive and strong bouncer.

It’s not because

the kids are lazy. It’s not because they don’t care. Well, they kinda don’t care. Why should they if they can

find the answer with a cell phone or really have no reason to use the skill? Actually sounds pretty healthy to me.

The Real Problem

The real

problem is the way we teach. I’ve read that there was a shift in the brain

after 9-11. With the unfiltered flood of information, kids had access to scenes

and images that normally are mediated by adults. Sure, we’ve known that the

information age changes who holds the information and that we can’t be the sage

on the stage.

Kids don’t

need us to tell them facts or give them information about anything. They don’t

need us to tell them if their answers are correct or not. You can google all that

s***. Used to, kids would listen to us anyway, fill out our workshits. They’d

sit nicely in class, wait for us to ask a question, wait for someone else to

call out the answer one at a time (or call out with several others in an unruly

group chorus), and then wait until we told them if that’s the answer we were

looking for or not.

I’m not sure

what’s continued to happen since 9-11, but kids are no longer willing to put up

with our instructional approach. They just don’t participate. Like, at all. And

when we ask them to think critically, we get mad at them because they can’t.

Lazy apathetic kids.

Explaining the solution: What I saw:

In the

lesson I observed, we were watching a Discovery video – well done and engaging–

about Frederick Douglass. Periodically, the teacher would stop the video and

ask questions. We’re supposed to do that right? Stop videos periodically to

check for understanding and teach? Yes. This is the sequence that followed when

the documentary displayed a copy of The Liberator,

a popular newspaper that Frederick consulted regularly once he reached freedom

in the north.

Teacher: What word do you see in the Headline?

Three kids randomly: Liberate, Liberty, Liberty

Teacher: One at a time. Raise your hand. Marissa?

Marissa: Liberty

Teacher: Yes. Liberty. What does that mean.?

Almost the whole class: Freedom!

Teacher: What does that tell you that this paper will be about?

Kids:

Teacher: If Frederick Douglass is reading this prior to the civil

war, what will the paper be writing about?

Long Pause.

Teacher: It starts with “sl…”

Kids: Slavery!

Teacher: Yes. (starts the video again)

Explaining the solution: What to do

instead?

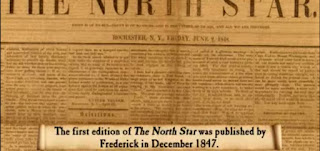

The teacher was

frustrated that she had to walk them through the same process the next time

when the documentary showed another newspaper called The North Star.

The kids didn’t know what topics would be in this

newspaper either. Even though she’d already talked them through how to figure

it out on the previous one. I’d never been successful in explaining what I meant

before, but this is what I tried:

Chaining:

Shona: So,

what you are doing here is called chaining. You broke the task into small

chunks that they could tackle one at a time. Each of your questions led to the

next one. But when you asked, “What word do you see in the title?” the kids

answered and were done with that question. They got it right. Moving on. They

didn’t realize that you were leading them through a sequence of questions. When

you asked the next question, “What does that mean?” they were answering a new

question with a right answer that was unconnected to the first one. And they still

didn’t know where you were headed with that question. Because that was only in

your head, not theirs. It's like you give them one link of the chain at a time and they don't know where they are going or what they are building.

You know where you are going and what you want them to

know, but they don’t. And that’s really

what you are teaching: how to use word meaning to understand text evidence and

author’s purpose. You are supposed to be teaching them how to think, but

you are the only one doing the thinking. That comes from an old philosophy of

behaviorism. That’s the way we were taught. That’s how we learned to teach.

That’s what our previous evaluation systems were based on. You were considered

successful if you could break things down into chunks that kids could manage one

bit at a time. And you're the only one holding it together.

Teacher: So

I’m not supposed to scaffold?

Me.

Interesting. Of course you are, but in a different way. You scaffold the

thinking, not the answers.

Teacher: I see

it. But what should I do instead? Tell me.

Scaffolding

with a Thought Chart

Me: I’ve

been thinking about this a lot, and I wonder if you thought about what a

scaffold really is. It starts at the bottom and goes up. You don’t climb it

from the bottom. What if your questions started at the bottom and went up? That

comes from a philosophy called constructivism. You scaffold by teaching the kids

about the thought moves and tools they use to climb up to the answer. They

construct the questions.

And in teaching

this way, finding the answer isn’t the point of the lesson. A scaffold is built

around a building or wall so you can work on the building or wall. Our work in

teaching must help kids past answering inference questions or word knowledge

questions. We must help them learn how to know that they need to ask a question,

know what questions to ask, and how to find those answers so they can do

thought work with the building – the text.

What if we start out with questions like these?

- How do we use word meaning as text

evidence to understand the author’s purpose and message and organizational/rhetorical

patterns? (What does the title of the newspaper tell you about its purpose and

topics that will be inside? What is the author if this documentary attempting

to convey with this graphic and point? Why would Frederick Douglass have been

reading this paper at this point in his life?)

- How do you know?

- What tools and knowledge do you use

to help you?

- How do you know if you are right?

Then, as we work

through the text, we create a thought chart, naming the things we can try. The

teacher and I brainstormed these ideas:

- Break

down words into their roots and parts (What do these words parts mean that

might help me understand?)

- Consider

the historical context and time period (How does the way this word is used fit

in with what was going on at the time?)

- Consider

the people and places referenced in the text (we stayed away from saying

Frederick Douglas’s name because we want the language to be generalizable and transferable

to the next time we encounter this type of skill)

- Consider

our background knowledge and gaps (research or question: What does the author

think I already knew? Where can I find the information that I don’t know about?)

- Personal

experiences or lack of experiences (What confirms or contradicts what I have

already experienced? Who can I discuss

this with or interview to find out more?)

- How

does this evidence fit in with the rest of the text? Why did the author include

this information in this way?

(We added

symbols after we realized that they didn’t have everything they need to examine

the next title in the documentary, The

North Star. But that’s the cool thing about thought charts – we can add to

them as we have more thoughts.)

Who’s in Charge of the Thinking?

If we help

kids develop the thought charts to guide their thinking through the meaning of

the title of the newspaper, The Liberator,

then they can use the thought chart to help them when the next title, The North Star, comes up in the

documentary. Then we aren’t the ones in charge of the questions. We aren’t the

ones telling them when to stop. We aren’t the ones telling them the answer is

right. We aren’t the ones getting mad because they can’t do something we

already chained them through with the first title.

We aren’t

the ones telling that they are dumb because they didn’t know that the north star

was used in concert with a sextant for navigation over sea. And that the north star

is key for orienteering over land. And that the north star is how slaves followed

the drinking gourd in the sky because the north star never changes position. And

that after that, the north star became a symbol associated with the

abolitionist movement. At some point, learning about the north star was your

first time too. Nobody got mad at you because you weren’t born knowing about it.

Nobody dismissed your intelligence and called you apathetic because you were

today years old when you figured it out.

Read Educated

to learn more about people who don’t know stuff and are still really smart. And

frankly, I’m tired of people telling me these kids don’t know anything and don’t

have any experiences. So disrespectful. These kids don’t have YOUR experiences,

but that doesn’t mean they are dumb. I was going to write this paragraph as a

parenthetical, but I realized that this thought is KEY to the message I am

trying to convey here. Kids aren’t dumb.

But the way WE are teaching can be.

When we chain…When

we ask about what a word means and don’t connect it to why we would even want to know what that word means…When

we are not transparent about what question we are really asking…When we make questions about finding a particular

answer…we are google. Nobody needs another google. Teaching is no longer about

answers and content and facts. Teaching is about thinking and reflection and

skills and processes to deal with

answers and content and facts. Stop chaining and start scaffolding. Don’t be google.

Be the North Star. Be the teacher

that shows them the way. Help them find their OWN north star.

Images from pixabay.