Tacy Gamel and I visited Leslee Justice's class a while back. After seeing how Leslee posted her objectives, Tacy wanted to create a resource that did the same with the ELPS statements. She took the I CAN statements from Donna ISD and placed them into this PowerPoint that you can print and post.

Tuesday, February 28, 2017

Wednesday, February 15, 2017

Solving Expository Woes

I think "woes" is my favorite word right now. Seems like it appears in every post. My friend Kim and I have been analyzing her students' papers. After placing the papers in score point stacks, we realized that each stack represented similar problems with development. Students were listing:

"Having a positive attitude is a thing that is a very successful think in your life. Having a positive mind is very enjoyable because you can do a lot more things in your life."

Students were repeating, adding nothing new.

"When you learn from lying, it can help you a lot. When you stop lying, people trust you more often. It helps if you don't lie a lot."

Students had paragraphs and reasons, but structure and development were missing.

We took apart one of the essays to examine the developmental patterns the writer was using.

We realized that the writer had a good hook. She also had a three pronged thesis. In the first paragraph we analyzed, we saw that she listed a pretty good reason. First, she added depth by giving a reason of when a person would need the detail referenced in the reason. Second, she listed a fact. The third sentence does not connect directly to the topic. It's true, but doesn't connect. The next two sentences lists a fact and an example, respectively. Pretty limited and unconnected development.

And can we tell you that explicitly naming the moves the writer was making was difficult for us? We had to do a lot of talking to decide exactly what the writer was doing. If we don't know what to call it...

Kim and I stared talking about how she was teaching development. She emphasized supporting details with this graphic.

What we realized: Students don't know what supporting details are. Students really don't know what we are talking about when we ask them to develop their ideas. How could we be more explicit with our students?

Julie Vick gave a wonderful presentation at the Abydos conference last week. We used her ideas for Conquering Coherence: Respond with Color! as a frame for our work.

Together, we created three models to revise this essay. The best way to improve to more advanced score points happens when we REVISE what we have already written. We wanted to create models that give students a clear picture of what we expect them to do.

2. Next, we created a model that uses pairs of CAFE SQUIDD to develop three main ideas/topics. (We did this because the original essay had a three pronged thesis. While we really don't recommend a five paragraph essay structure often, this writer chose to do so. In addition, sometimes kids don't have much to say about the topic. They need the flexibility of more reasons to support their ideas.)

While creating this model, we wrote down the thesis, then immediately composed the main idea sentences that offered reasons for the thesis. Then we read the main idea sentence and referenced the CAFE SQUIDD chart. We asked ourselves: What two CAFE SQUIDD pairs seem to match what we could say about this idea? It was important to pick two. We made a statement and then used a second one to develop the idea presented in the previous statement.

Some things to note.

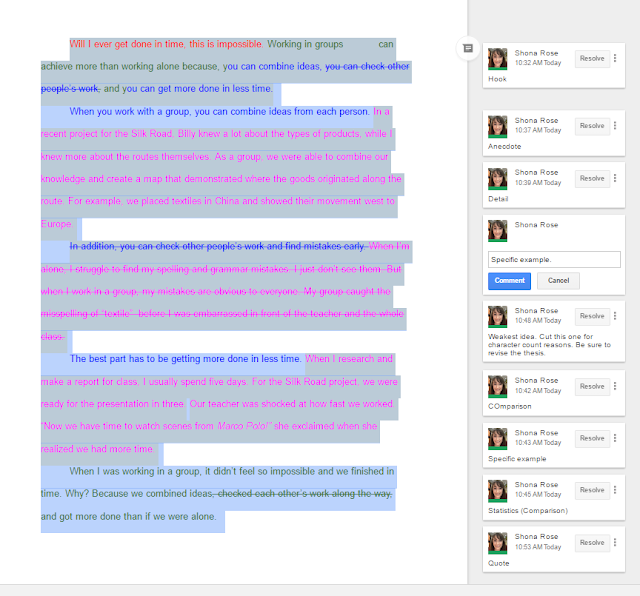

3. Finally, we realized that sometimes, writers can use text structures to organize the whole essay. We decided that comparison would fit well with this topic. We decided to create two paragraphs, one for working alone and one for working with a group. After we composed the first paragraph, we used that paragraph to match, point by point, the comparison to working as a group. We used pairs of CAFE SQUIDD here as well.

Here's the link to the google docs so you can see the comments more closely.

"Having a positive attitude is a thing that is a very successful think in your life. Having a positive mind is very enjoyable because you can do a lot more things in your life."

Students were repeating, adding nothing new.

"When you learn from lying, it can help you a lot. When you stop lying, people trust you more often. It helps if you don't lie a lot."

Students had paragraphs and reasons, but structure and development were missing.

We took apart one of the essays to examine the developmental patterns the writer was using.

And can we tell you that explicitly naming the moves the writer was making was difficult for us? We had to do a lot of talking to decide exactly what the writer was doing. If we don't know what to call it...

Kim and I stared talking about how she was teaching development. She emphasized supporting details with this graphic.

What we realized: Students don't know what supporting details are. Students really don't know what we are talking about when we ask them to develop their ideas. How could we be more explicit with our students?

Julie Vick gave a wonderful presentation at the Abydos conference last week. We used her ideas for Conquering Coherence: Respond with Color! as a frame for our work.

Together, we created three models to revise this essay. The best way to improve to more advanced score points happens when we REVISE what we have already written. We wanted to create models that give students a clear picture of what we expect them to do.

- In the first essay model, we used CAFE SQUIDD to develop an essay that utilized only ONE main idea: (Note - the thesis is green. Main idea/topic is blue. Pink is development.)

2. Next, we created a model that uses pairs of CAFE SQUIDD to develop three main ideas/topics. (We did this because the original essay had a three pronged thesis. While we really don't recommend a five paragraph essay structure often, this writer chose to do so. In addition, sometimes kids don't have much to say about the topic. They need the flexibility of more reasons to support their ideas.)

While creating this model, we wrote down the thesis, then immediately composed the main idea sentences that offered reasons for the thesis. Then we read the main idea sentence and referenced the CAFE SQUIDD chart. We asked ourselves: What two CAFE SQUIDD pairs seem to match what we could say about this idea? It was important to pick two. We made a statement and then used a second one to develop the idea presented in the previous statement.

Some things to note.

- The original essay had a hook. That is displayed in red. Kim and I think that we might be spending more time on a hook than necessary. If you have a good one, fine. But the most important thing to do in 26 lines or 1250 characters is to have something meaningful to say in the body of the paper. The rubric privileges development, not interesting beginnings.

- When we used the CAFE SQUIDD pairs, we realized that we used too many characters. We looked back at the paper to find the weakest point. Then we pressed delete. (Actually, I learned that you can press alt, shift, and 5 to make a strike through.) Then we realized that we needed to revise the thesis to remove the idea we didn't use.

3. Finally, we realized that sometimes, writers can use text structures to organize the whole essay. We decided that comparison would fit well with this topic. We decided to create two paragraphs, one for working alone and one for working with a group. After we composed the first paragraph, we used that paragraph to match, point by point, the comparison to working as a group. We used pairs of CAFE SQUIDD here as well.

Here's the link to the google docs so you can see the comments more closely.

Master Teacher: Leslee Justice's Annotation Lesson for Old Major's Speech

Some of you will remember the English II class I visited in Canyon a couple of weeks ago. I asked her to pull together some resources for you about the lesson we watched. This teacher - DANG -probably the best example of technology integration, clear objectives, scaffolded instruction and feedback that I have ever witnessed. Below, Leslee Justice recreates the experience for you - links, annotations, documents and resources!

Merry Christmas,

Shona

Merry Christmas,

Shona

Annotation Lesson - Old Major’s Speech

Animal Farm

|

Lesson Objectives:

Students will be able to identify and analyze the three main rhetorical appeals, pathos, ethos, logos in a fiction text.

Students will be able to analyze and academically discuss the author’s use of rhetorical appeals using sentence stems.

Students will be able to identify and analyze the use of rhetorical appeals in a secondary text.

Students will be able to critically analyze a text and use text evidence to support their thinking.

Day One:

Students are introduced to rhetorical appeals and take notes on their definition and meaning. I introduce this material with a short video and class discussion.

Students then practice identifying the rhetorical appeals in a speech made by President Obama. Students practice explaining his use of the rhetorical appeals with a partner.

After students are comfortable with the basics of rhetorical appeals. I then provide them with a copy of Old Major’s speech from Animal Farm. Students will do a basic annotation for fiction and answer the questions I have provided for them. We have been doing these types of annotations all year so they are pretty comfortable with them. They are not annotating for pathos, ethos or logos. I simply want them to have a deep understanding of the text and the purpose it plays in the overall novel.

Day Two:

To begin today we review rhetorical appeals using an anchor chart and the contents of Old Major’s speech. I then walk students through my own annotation of the text using a previously recorded video. This allows students to stop and take notes, as well as replay what I have said. As I annotate, I try to pull students away from just identifying the rhetorical appeals and into a deeper level of analysis. This is always extremely difficult for my students and takes several examples before they really understand the process.

After students have finished watching the annotation video they then begin to discuss the speech in small groups using sentence stems. These thinking stems are from Lead4ward and I just filled in the blanks so that they would apply to Old Major’s speech. You could do this with any text. This allows the discussion to move from a superficial level of summary and identification to analysis.

As students are discussing the speech, I walk around to hear their conversations and quickly correct misunderstandings. I am not only focused on rhetorical appeals but also on their general understanding of the text.

To assess their understanding I ask them to identify the most powerful rhetorical appeal and its effect on the audience in the text using the “write around strategy”.

Day Three:

After students have spent two days identifying rhetorical appeals and analyzing Old Major’s speech I move them onto a harder speech. Due to the timing of our lesson I used President Trump’s Inauguration speech as a secondary text for students to practice their analysis on. They went through the annotation process again and then completed a two part short answer question.

Short answer questions for student response:

1. On which rhetorical (pathos, ethos, logos) does President Trump rely the most? Why do you think this was his choice? PROVIDE TEXT EVIDENCE to support your thinking.

2. In what ways are President Trump's speech similar to Old Major's? In what ways are they different? Use TEXT EVIDENCE FROM BOTH.

2. In what ways are President Trump's speech similar to Old Major's? In what ways are they different? Use TEXT EVIDENCE FROM BOTH.

This short answer allows me to see if students understand the basics of rhetorical appeals and can provide a deeper level of analysis. I also grade their annotations to see if their thinking has been made visible during their reading.

Tuesday, February 14, 2017

Words or Actions: Are you racist or biased?

Words

or Actions

When

I was growing up in Amarillo, my mother surprised me with the shocking revelation

that my 3rd grade teacher was not white. Unbelieving, I marched

my skinny legs back to the school to confront my teacher. “Mrs. Avery, my momma says that

you’re black.” (That’s the language we used back then if you remember the

60’s.) “I told her she was lyin’ ‘bout you!” The teacher

grinned, chuckled, and taught me another lesson. “Honey, your momma is

right. I am black. But that doesn’t really matter in third grade, does

it?”

I attended a recruiting event recently. In the back of the room, I met two timid, yet

articulate and passionate women of color. They didn’t have an invitation to the event, but they took a risk to seek out those in leadership

about how they could become involved in serving the organization. Of course they were welcomed, but perhaps

I was reminded of our responsibility and the moral imperative to seek

out and develop those who can serve the changing

demographic needs of our society.

After reflecting with a friend, she shared an analogy presented by her mother, “I am never unaware of being a

woman. When I wake, I have specific garments that define my gender. There are

cycles and activities only a woman enjoys.” To those who are minorities around us, surrounded by faces and cultures so unlike

theirs, are they ever unaware of their differences? I'm pretty sure that some are never unaware that I am white, even if I wasn't raised to see them any differently than myself.

Tracy Winstead, of Northside ISD in San Antonio, shared her Diamond re-certification research about Culturally Responsive Teaching last week. Brilliant. She encourages us to examine our own Cultural Reference Points to become more aware of our own - even unintentional - biases. "Some of this is voluntary until you encounter a situation where you are 'exposed' to yourself. It's not racist, but it is bias," Tracy Winstead.

Here are the handouts to the session, bibliography included. Ignore or forgive my notes.

Thursday, February 9, 2017

When Kids aren't Growing in Guided Reading: Matthew

On Monday, I worked with some incredible teachers at Crockett Elementary in Borger.

We started out the morning by using one of Gretchen Bernabei's kernel essay formats to direct our thinking about kids who were not growing in their guided reading groups.We used the "Picking Up the Pieces" model.

As a heading, write the name and level of a student in your class that is not growing.

1. What happened? On the first sticky note, write about what the student was doing in the last running record. What kind of errors did the student make?

2. Why didn't you see it coming? What have you already tried with this student?

3. What damage does this cause? What impact does the student's reading behaviors have on comprehension, predictions, inferences, summary, etc.?

4. What will you/did you do? What did yo try for your teaching point or intervention?

After teachers had time to share their thinking, each teacher brought forward a student to the group for problem solving.

Matthew is a bilingual (ish) student who struggles with being able to break words apart, remembering characters (their names), and remembering the sounds that letters make. His teacher reports that he cuts off endings and doesn't really have many strategies to make sense of what he is reading. She says that you can tell that he "feels behind" and is easily frustrated.

First, we coded the errors that he made by which cues he was using and which he was neglecting.

colors for clues

Matthew appears to be using visual cues to solve. He is looking at the beginning and end of the word. He sees the high point in the word with the letter l. His miscue fits structurally as it is makes sense in terms of grammar. Both words are plural nouns. What he isn't doing is using meaning. Colors doesn't make sense in terms of what came before in the sentence or in context of the story he was reading. What he isn't doing is using smooth tracking all the way through the word. He's looking at the whole word as a chunk rather than attending to a smooth tracking through all the letters in the word.

We also discussed that he might not be pronouncing the blend cl correctly. "/kuh/ /l/" sounds more like the beginning of /kulors/ than /kloos/.

water for weather

The same analysis for the previous miscue applies here as well. In addition, he appears to be reading consonants and disregarding vowel pairs, ue from the previous miscue and ea from this one.

might for may

This one fascinated me. The bilingual teacher in the group - not the child's teacher - pointed out that in Spanish, you pronounce the word "may" as /my/! We would never have known that if we were not collectively using our expertise and experience as a group to discuss how to help this child. In this case, the child was using initial visual cues, structural cues, and meaning cues that included the schema from his Spanish influences.

Initial look at the miscues led us to think that the child was having trouble with decoding. Previous attempts to support the child focused on helping the child focus on the visual features of the word. It wasn't until we coded the miscues and analyzed the patterns that we saw the truth.Yet, when we looked at the miscues for patterns of error, we noticed that the child never corrected himself. He had no awareness that his miscues did not make sense!

He needed to attend to meaning first, then cross check for visual and smooth tracking through the word to help him solve at the point of his difficulty.

Here's the response we decided needed to occur for the teaching point or intervention:

After the student read, go back and read the sentence to the student as he read it. Ask, "Did that make sense?" and discuss. What word didn't make sense? In this text, the miscue was /colors/. " What word might fit the story better?" Discuss. "I want you to notice when things don't make sense. Can you stop next time that happens? Let me show you what you can do if something doesn't make sense. Go back to the beginning of the sentence and reread until you get to the part that doesn't make sense. That will get your brain thinking about the story again. Now, we can stop and think."

"When you read it the first time, you said /colors/." Write that word or use magnetic letters. Use slow articulation as you write or push the letters into Elkonin boxes while you stretch out the sounds.

Next, go to the word in the text. In this instance, the word is clue. Cover the word with a popsicle stick. "If this word was colors, what letter would come first?" Accept the answer and uncover. Keep going for each of the letters/sounds until there is a discrepancy. In this instance, the child will notice immediately that colors and clue aren't matching. Keep uncovering the letters one or two at a time, depending on the blends or vowel cues that might need support. "Good readers, see all the letters in the word. Their eyes track smoothly across the word from the beginning to the end. It might be easy to miss a word if you are only looking at parts of it." Circle the letters that are similar - c/l/s. Notice that Matthew did this in the word /weather/ as well.

Now use the techniques to bring a word to fluency. (I guess I'll have to write about that later.)

This teaching point is going to help him with self correcting for meaning and cross checking for visual at the point of difficulty. This might just be the key to moving him to the next level very quickly.

What we learned: When kids aren't moving, bring the kid before your PLC for problem solving. Talk to your curriculum person. Or text/email me. Together, we can find solutions.

Thursday, February 2, 2017

Essential Lesson Structures: Going to the Movies with Paired Verbal Fluency

Essential Lesson Structures: Going to the Movies with Paired Verbal Fluency

Part One: Exploration and Gathering Information

- Read the text. You may read alone, in a partner, or with a group as your teacher sees fit.

- What questions are you thinking about at the end of this reading? What are you wondering about? What is confusing or unclear?

- Powerful passages: What sections of the text caught your attention? This could be something surprising, weird, or well said.Make a note of the page number and beginning words so you can read it to your group. Be sure to write why you chose it.

- Connections: What personal events were you reminded of in this reading? Are there other books you have read that connect with this story or information? How?

- Sketch: Make a simple picture or diagram that represents this reading to you. Remember that what’s important is not your artistic ability—it’s your ideas.

Part Two: Consolidation and Collaboration

- Meet with your group and discuss the text.

- Using only images, create a poster that conveys the major concepts of the text. Prepare an oral explanation or retelling. Record the page numbers or headings from the text at the top of your poster.

- Post your images on the wall in order as they appear in the text.

Part Three: Refining and Reflecting

- Present your findings to the class. Listen closely to all presentations, as you will be expected to replicate the information.

- Be ready to present: Someone needs to be “at bat” to present. The next person “at deck” ready to step in when the person before has completed their presentation. A third person needs to be “in the whole” and in place. Watch the order so you will know when to get into position.

- Paired Verbal Fluency: After everyone has presented, please meet with a partner to follow these instructions:

- Decide who will be speaker #1 and who will be speaker #2.

- Beginning with the first poster, the first speaker recalls and summarizes the main ideas.

- When the timer goes off (or the signal word “switch” is used), speaker two continues summarizing without repeating previous information.

- Continue until time is called.

- Note: “Three to four rounds are usually sufficient. The time for each partner usually should not exceed forty-five seconds. Decreasing the time for each round keeps the energy high. We usually use three rounds of forty-five seconds, thirty second, and twenty seconds. At the end of the paired verbal activity, you may wish to allow pairs a few more minutes for true conversation about the topic at hand” (pg 80 from How to Make Presentations that Teach and Transform, ASCD, 1992).

Part Four: Whole Class Debrief

- As a class, debrief the salient ideas. Consider ending with intention statements:

- I will…

- I intend…

- No matter what…

- I promise…

- As a class, debrief the experience in terms of social and behavioral collaboration. Consider: What worked well? What needs improvement?

Adapted from Learning Forward: The Professional Learning Association’s “Tips and Tools”

Essential Lesson Structures: Comprehension Card Sort

Essential Lesson Structures: Comprehension Card Sort:

Part One: Exploration and Gathering Information

- Scan the material for headings, topics, highlighted words, boldfaced words, italicized words, etc.

- (For nonfiction) Prioritize the sections in the material. Which sections of the text seem to have significance or importance to you personally? Scan these sections for specific information.(For fiction) Read through through the text as a whole. Then go back to sections that surprised you, confused you, or confirmed what you already knew.

- Using note cards, write one thought, definition, important point, etc., per card from the information you are reading.

- If time permits, read sections you have not perused.

Part Two: Consolidation and Collaboration

- Collect the cards from those in your group.

- Stack, shuffle, and deal the cards to each member until they are all gone.

- One at a time, read aloud what is written on your card. Lay the card face up on the table. Do not stack the cards. All cards should be exposed so they are visible to everyone at the table.

- Categorize the cards into major topics by similarity or main idea.

- Using a different color of note card, label the categories. Make a table display so that all information can be viewed.

Part Three: Refining and Reflecting

- Working alone or as a table group, visit the other tables to see their displays.

- Discuss and annotate your document for key ideas new to your group or your own thinking.

- Reflect: What information did you see on most tables? What information did you see what was not included at your table? What is/are the most important thing(s) that you learned?

Part Four: Whole Class Debrief

- As a class, debrief the content of the text. Consider using the What, So What, Now What Format.

- As a class, debrief the experience in terms of social and behavioral collaboration. Consider: What worked well? What needs improvement?

Adapted from Robert J. Garmston and Bruce M. Wellman Presentations that Teach and Transform ASCD (1992).

NOTE: Aimee Coates and I adapted this strategy for the Anne of Green Gables text. We decided that we would give the labels that we wanted to give the kids to use in categorizing their ideas from the text. Technically, this is called a "closed sort."

NOTE: Aimee Coates and I adapted this strategy for the Anne of Green Gables text. We decided that we would give the labels that we wanted to give the kids to use in categorizing their ideas from the text. Technically, this is called a "closed sort."

Then we had the kids take the stack with the exposition and compare them with other elements. I think it would be really easy to make a T chart and list piece of text evidence that could be directly traced back to something that was introduced in the introduction. We thought of a new question too: How do Anne's character traits complicate the problems with her aunt?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)