Thursday, August 31, 2017

Inference Hooey: Part III Addressing Process to Make the Text Cohere with Sentence Combining and Deconstructing

Syntax Surgery seemed to really make the thinking processes visible for making inferences. Sentence Combining and Sentence Deconstruction work well to help comprehension coherence as well.

Sentence Combining:

I learned about sentence combining from Killgallon and Noden. But again, this work was not woven into what I understood about teaching comprehension. I used it to help students write better.

Here's some permutations and options.

Before reading:

1. Preview the text and select a sentence that is syntactically complex: (These are the examples from the Reading Academy, slide 29.)

He wanted to slide down to the floor and speak to her, but he didn't dare.

She was wearing a white sweater, tweed skirt, white wool socks, and sneakers.

2. Break the sentence into multiple sentences. Write them on sentence strips.

He wanted to slide down to the floor.

He wanted to speak to her.

He didn't dare.

She was wearing a white sweater.

She was wearing a tweed skirt.

She was wearing white wool socks.

She was wearing sneakers.

3. Ask students to use what they know to combine the sentences meaningfully. Have students read their combinations aloud. Discuss the connotations and implications of those combinations. (It doesn't make much difference in the sentence with items in a series, but the way you combine the first example changes the meaning by changing the context/scene.)

4. If you want to explore specific grammatical features such as compounding or subordination, offer those elements on index cards and ask students to use them when they combine the sentences.

5. Reveal the original sentence and discuss. Make predictions about the text.

After Reading:

1. Reveal the original sentence from the text.

2. Ask the students to break the sentence into parts.

3. Discuss the changes, craft, and impact.

4. Have students enter a piece of their writing to find a place where they have choppy or repetitive sentences like the deconstructed sentences. Have students imitate the way the original sentence was combined. Or have students find a place in their writing where they have already included the feature in the original sentence. Have them check for punctuation and logical coherence.

Sentence Deconstruction:

I did NOT know about this strategy. During the reading academy, there were many aha's when we revealed the insights present in what was missing from the sentences. See if you feel the same way. Sometimes kids don't comprehend, because they don't see things that are implied, or that are just common sense in the sequence of events. This is particularly evident when passive voice is used. Who is doing the action?

During Shared Reading:

1. Find a sentence with a syntactic element that is complex. It should be one that you would like like to practice using.

2. Display the original sentence.

3. Model how breaking apart a sentence like this reveals things that are implied, or understood, by the reader.

Original Sentence:

After two days, the cement was dry, and the wooden structures were broken down and taken away, leaving the dried cement blocks.

4. Show students how to deconstruct the ideas present in the original sentence.

two days

the cement was dry

wooden structures were broken down

and taken away

leaving the dried cement blocks

5. Work through each of the ideas, making a complete sentence. Fill in the /who/subject/ or what/verb/ that is missing from each idea.

The workers waited two days. (The workers, the people doing the action, are never mentioned in the original sentence.)

The cement was then dry. (shows the cause and effect relationship of why they waited)

The workers [broke] down the wooden structures.

They [the workers] [took] the wooden structures away.

They [the workers[ [left] the dried cement blocks.

The dam was finished. Implied.

It ASTONISHES me how much is missing in the sentence. No wonder kids have trouble teasing out the meaning and coming to the inference implied by the sentence.

This process won't need to be done every time, but wouldn't it make you feel better to know that nothing's wrong with you when you read? Wouldn't it make you feel better to realize specifically what the teacher means when she asks you to read between the lines? The stuff in RED makes that silly statement mean something that you can use when you read. You can break the sentence into idea units and then fill in what's missing. This kind of thinking is a process we all go through, but deconstructing the sentence and filling in the missing pieces like this makes that process concrete and visible instead of ephemeral and unattainable for those who struggle.

Inference Hooey: Part Three: Addressing Process for Making the Text Cohere with Syntax Surgery

Making the text cohere involves two categories:

- Readers must connect words and phrases as they read to ensure the text sticks together and makes sense.

- Readers must use syntactic knowledge to make sense of complex phrasing or sentence structures.

If those two things are true, then teachers need to have specific understandings and lessons to show students how to do this kind of thing. Honestly, when I first read this slide, I understood what it meant in a technical way. I know what all the words mean. But as a reader, I didn't have an understanding of what I am doing in my mind to make the text cohere. Frankly, I don't ask myself or think about cohesion at all when I read. I think about cohesion when I am evaluating something that I have written or when I am evaluating something a student wrote. Cohesion is something on my grading rubric. I had not considered cohesion as an element of inference and reading comprehension.

During the reading academy here at Region 16, the participants thought the same thing. We believe there is merit here, but we know that we need to think about it more.

(It's also connected to prosody...I wrote about that here: Prosody, Multiple Meaning Words, and Lighting a Fire with Anna)

Connecting Words and Phrases: One of the solutions proposed in the Reading Academy was Syntax Surgery. Beers has excellent examples in her book When Kids Can't Read, What Teachers Can Do on pages 70-71 and 135-136.

This resource, shows a good example of what the strategy looks like with text:

While this is a great example, sometimes teachers don't know exactly what needs to be pulled from text for these kinds of conversations. My first piece of advice is to listen to students read aloud. When their prosody, or phrasing, is off - that's probably what needs syntax surgery. There's probably some syntactical, grammatical, or mechanical feature there that is tripping up comprehension.

Second, there are things in text that we know mess kids up. Here's a list:

1. Modifiers: In Reading Recovery, and some Guided Reading models, kids are taught to problem solve up to the point of difficulty. With nuanced text, that doesn't always work. Sometimes you need to keep reading to know how to phrase the text. This is particularly true with words we normally perceive as nouns that serve as modifiers. Here's the example from when I was reading Hatchet with Anna:

2. Appositives: We need to tell kids - explicitly - how appositives work. And we need to show them in multiple places in a sentence.

3. Connectives: Connections are not always apparent until they are explicitly pointed out. Noticing them significantly brings for the meaning intended by the author. In the case below, the author is making a contrast. Even though the character is experiencing the end of school - which most people think is the end of studying - he is embarking on a new journey of learning. The words "although," "finishing," and "beginning" all work together to create the contrast.

4. Pronouns and Referents: Kids lose track of characters, people, and referents to things. In the passage below, the antecedents are written correctly, yet there is still an opportunity to get confused about exactly what the pronoun "they" referenced. Drawing arrows to keep references to scientists separate from living things can help kids keep the concepts separate.

5. Subject-verb agreement: This is especially important when single/compound subjects are separated from the verb. Students need to understand the connections between the words in terms of meaning as well as how to orally phrase with the interruption indicated by the punctuation.

6. Subjects and compound predicates: These can be separated as well. Students need to realize that all three of these actions are completed by the parents -even though their daughter didn't want them to.

7. Coordinating or Correlative Conjunctions: These make distinctive differences in meaning, depending on which one of the FANBOYS or other terms are used. In the case below, there is a contrast between the characters as well as a distinction between their baked goods.

8. Subordinating Conjunctions: Illuminating conditional elements, subordinating conjunctions reveal importance and significance.

9. Modifying Phrases and Clauses: As sentences become more complex, clauses and phrases extend both subjects and predicates. Kids can get lost in what belongs with what.

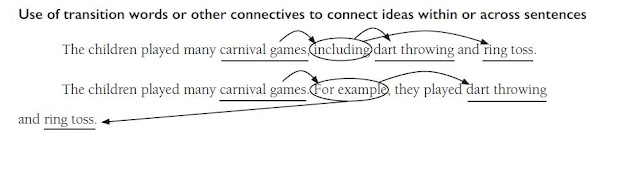

10. Transitions and Connectives: Sometimes, we think kids know what these words mean. But often they don't. That's the first hurdle. Being able to segment and connect the parts they combine is the next.

11. Authors vary terms, especially when the concepts are repeated in the same sentence. Sometimes, these words are additional context to help students identify meaning. Other times, its an element of craft.

12. And sometimes...something's missing.

13. And because 13 is my favorite number. And because Paulsen is my favorite author. And because I just love the dash...

Sometimes, prosody reveals the comprehension wolf. Understanding what it reveals through Syntax Surgery makes us realize that making sense of things is just another normal part of reading.

Sentence examples come from Handout 10, Syntax Surgery: Connections to make from the Grade 5 Reading to Learn Academy Materials prepared by The University of Texas System/Texas Education Agency.

Sentence examples also come from Gary Paulsen's Hatchet.

Wednesday, August 30, 2017

Prosody, Multiple Meaning Words, and Lighting a Fire with Anna

Anna is in the 4th grade this year. Their mentor text is Hatchet. Which happens to be one of my favorites. After Kevin and Chris Swanson from Durham Intermediate in Southlake introduced me to those books, I have often said that I would marry Gary Paulsen if he wasn't already married.

And after reading with Anna, I love him even more.

Trying to read the book independently, Anna came into the living room crying. She didn't understand a thing. And after reading aloud with her, I understood why. Here are some of the moments that brought me joy.

"On the dashboard in front of him, Brian saw dials, switches, meters, knobs, levers, cranks, lights, handles that were wiggling and flickering, all indicating nothing that he understood and the pilot seemed the same way. Part of the plane, not human" (Hatchet, p. 3).

It wasn't too much later that I realized Anna felt the same way about reading. On the paper unfolded before her, Anna saw letters, words, syllables, lines, paragraphs, quotes, and page after page that were confusing and fickle, all indicating nothing that she understood and the joy of it seemed the same way. Part of the book, not herself.

As we read, I realized that there were patterns in her confusion.

Multiple meaning words and context:

"He had never flown in a single-engine plane before and to be sitting in the copilots seat with all the controls right there in front of him, all the instruments in his face..." (pg. 2).

Anna interrupted.

"Nona, what in the world are instruments doing in his face? I thought he was in a plane." Anna didn't have the schema or vocabulary for a single-engine plane. Just like Brian, the experience was foreign. She was using her existing schema and strategies to understand, but the cognitive dissonance and mental image of a violin in Brian's face wasn't quite working for her. While reading alone, she didn't have the resources to realize why it wasn't making sense. She thought the problem was with her.

I pulled out my phone and googled pictures of a single-engine plane. We pointed and talked about the cockpit and then arranged ourselves on the couch as if I were the pilot and she were Brian. As we read, we each played our part - making the actions or facial expressions indicated by the text.

But I can't tell you how many times the multiple meaning words have interfered: nose (of the plane), calf (with the porcupine quills), belt (of bushes around the lake), chip (in the ax), weak (sparks), and so on. She began to learn to stop and ask some questions when her mental image didn't match the context.

Prosody:

The most interesting experience, however, was Palusen's way of "speaking," his voice, his long sentences, his short ones, his clauses within clauses, his dashes. The authentic way we speak and think doesn't match the simple sentence patterns we learn about in grammar. And Paulsen doesn't patronize us with such limiting syntax. But this requires a nuanced understanding of phrasing and emphasis that Anna didn't know how to do.

I often begin teaching prosody to adults by sharing this sentence.

THE OLD MAN THE BOAT.

Some will tell me that it isn't a sentence, but a list of two things: a man and a boat. If the sentence is not read with prosody, it makes no sense.

The old (as in old people) man (as in navigate) the boat.

That's a sentence.

And it doesn't make much sense without prosody. The same thing happens when kids are reading. Often, we can tell if they understand what they are reading by what they are stressing and how they are phrasing and chunking pieces of the text together. Here are some of the phrases that jumped out at us:

Prosody with Modifiers:

"One of the pilots, a woman, had found some kind of beans on a bush and she had used them with her lizard..." (pg. 61). Anna's voice went down to end the sentence. "With her lizard" was a completely logical semantic unit.

"Nona! Why would she use the beans with her lizard?"

I chuckled. "You phrased that exactly right." I repeated what she had read. "But sometimes, the way you make your voice sound doesn't make sense when you read the next word. Listen: 'One of the pilots, a woman, had found some kind of beans on a bush and she had used them with her lizard meat to make a little stew in a tin can she had found. Bean lizard stew.'" And of course, we laughed.

It happened again a few pages later. We had been trading every other sentence. This time I was reading. "The pain had gone from being a pointed injury..." my voice trailed off and then I saw the next word: pain. Injury was modifying pain, not serving as the noun! I started the sentence over and read, "The pain had gone from being a pointed injury pain to spreading in a hot smear up his leg and it made him catch his breath."

"Nona! You mean even you say stuff wrong when you read?" Yes, dear. I do.

Prosody with Punctuation:

"He didn't want to be away from his - he almost thought of it as home - shelter when it came to be dark." Sometimes, Anna, the author is surprised by something he is thinking in the middle of his thought. He uses dashes to show this revelation. It's kind of like an interruption. I read the thought aloud and then asked her to read the interruption and then I finished the sentence. Every time we saw one of those dashes after that, we started trading voices to emphasize the phrasing, the interruption.

Putting Prosody and Monitoring for Word Meaning Together:

After Brian's interaction with the porcupine, he has a dream that he can't interpret. I knew that we had the evidence we needed to come to the conclusion Brian was about to discover before Paulsen revealed it. We stopped after this sentence: "Something came then, a thought as he held the hatchet, something about the dream and his father and Terry, but he couldn't pin it down." Anna had been struggling to understand the dream earlier and I pushed her.

"Anna, we have what we need to figure this out." I started to flip backward to reread the paragraph where Brian throws the hatchet and the sparks fly. She groaned in disappointment, "Again? Uggh."

And then something magical happened. You can hear it here: start at 15:50 and listen to about 17:20. Then skip to 20:00 and listen until you hear her figure it out.

Anna: [Gasps]

Me: What just happened in your mind just now.

Anna: He wants to have a fire.

Anna: But he doesn't have it

Anna: He doesn't know how to make it.

Anna: That's all.

Anna: I know he doesn't know what his dad was doing.

Me: What happened when he threw the ax...

Anna: [MAGIC HAPPENS]

I knew then that she was ready to read the next chapter on her own. We watched a couple of videos about starting a fire, previewed a few words, and I set her off to read on her own. It wasn't much longer until she bounded back into the living room, pages of the book flapping like brittle kindling, her face burning with the joy of chapter nine.

And after reading with Anna, I love him even more.

Trying to read the book independently, Anna came into the living room crying. She didn't understand a thing. And after reading aloud with her, I understood why. Here are some of the moments that brought me joy.

"On the dashboard in front of him, Brian saw dials, switches, meters, knobs, levers, cranks, lights, handles that were wiggling and flickering, all indicating nothing that he understood and the pilot seemed the same way. Part of the plane, not human" (Hatchet, p. 3).

It wasn't too much later that I realized Anna felt the same way about reading. On the paper unfolded before her, Anna saw letters, words, syllables, lines, paragraphs, quotes, and page after page that were confusing and fickle, all indicating nothing that she understood and the joy of it seemed the same way. Part of the book, not herself.

As we read, I realized that there were patterns in her confusion.

Multiple meaning words and context:

"He had never flown in a single-engine plane before and to be sitting in the copilots seat with all the controls right there in front of him, all the instruments in his face..." (pg. 2).

Anna interrupted.

"Nona, what in the world are instruments doing in his face? I thought he was in a plane." Anna didn't have the schema or vocabulary for a single-engine plane. Just like Brian, the experience was foreign. She was using her existing schema and strategies to understand, but the cognitive dissonance and mental image of a violin in Brian's face wasn't quite working for her. While reading alone, she didn't have the resources to realize why it wasn't making sense. She thought the problem was with her.

I pulled out my phone and googled pictures of a single-engine plane. We pointed and talked about the cockpit and then arranged ourselves on the couch as if I were the pilot and she were Brian. As we read, we each played our part - making the actions or facial expressions indicated by the text.

But I can't tell you how many times the multiple meaning words have interfered: nose (of the plane), calf (with the porcupine quills), belt (of bushes around the lake), chip (in the ax), weak (sparks), and so on. She began to learn to stop and ask some questions when her mental image didn't match the context.

Prosody:

The most interesting experience, however, was Palusen's way of "speaking," his voice, his long sentences, his short ones, his clauses within clauses, his dashes. The authentic way we speak and think doesn't match the simple sentence patterns we learn about in grammar. And Paulsen doesn't patronize us with such limiting syntax. But this requires a nuanced understanding of phrasing and emphasis that Anna didn't know how to do.

I often begin teaching prosody to adults by sharing this sentence.

THE OLD MAN THE BOAT.

Some will tell me that it isn't a sentence, but a list of two things: a man and a boat. If the sentence is not read with prosody, it makes no sense.

The old (as in old people) man (as in navigate) the boat.

That's a sentence.

And it doesn't make much sense without prosody. The same thing happens when kids are reading. Often, we can tell if they understand what they are reading by what they are stressing and how they are phrasing and chunking pieces of the text together. Here are some of the phrases that jumped out at us:

Prosody with Modifiers:

"One of the pilots, a woman, had found some kind of beans on a bush and she had used them with her lizard..." (pg. 61). Anna's voice went down to end the sentence. "With her lizard" was a completely logical semantic unit.

"Nona! Why would she use the beans with her lizard?"

I chuckled. "You phrased that exactly right." I repeated what she had read. "But sometimes, the way you make your voice sound doesn't make sense when you read the next word. Listen: 'One of the pilots, a woman, had found some kind of beans on a bush and she had used them with her lizard meat to make a little stew in a tin can she had found. Bean lizard stew.'" And of course, we laughed.

It happened again a few pages later. We had been trading every other sentence. This time I was reading. "The pain had gone from being a pointed injury..." my voice trailed off and then I saw the next word: pain. Injury was modifying pain, not serving as the noun! I started the sentence over and read, "The pain had gone from being a pointed injury pain to spreading in a hot smear up his leg and it made him catch his breath."

"Nona! You mean even you say stuff wrong when you read?" Yes, dear. I do.

Prosody with Punctuation:

"He didn't want to be away from his - he almost thought of it as home - shelter when it came to be dark." Sometimes, Anna, the author is surprised by something he is thinking in the middle of his thought. He uses dashes to show this revelation. It's kind of like an interruption. I read the thought aloud and then asked her to read the interruption and then I finished the sentence. Every time we saw one of those dashes after that, we started trading voices to emphasize the phrasing, the interruption.

Putting Prosody and Monitoring for Word Meaning Together:

After Brian's interaction with the porcupine, he has a dream that he can't interpret. I knew that we had the evidence we needed to come to the conclusion Brian was about to discover before Paulsen revealed it. We stopped after this sentence: "Something came then, a thought as he held the hatchet, something about the dream and his father and Terry, but he couldn't pin it down." Anna had been struggling to understand the dream earlier and I pushed her.

"Anna, we have what we need to figure this out." I started to flip backward to reread the paragraph where Brian throws the hatchet and the sparks fly. She groaned in disappointment, "Again? Uggh."

And then something magical happened. You can hear it here: start at 15:50 and listen to about 17:20. Then skip to 20:00 and listen until you hear her figure it out.

Anna: [Gasps]

Me: What just happened in your mind just now.

Anna: He wants to have a fire.

Anna: But he doesn't have it

Anna: He doesn't know how to make it.

Anna: That's all.

Anna: I know he doesn't know what his dad was doing.

Me: What happened when he threw the ax...

Anna: [MAGIC HAPPENS]

I knew then that she was ready to read the next chapter on her own. We watched a couple of videos about starting a fire, previewed a few words, and I set her off to read on her own. It wasn't much longer until she bounded back into the living room, pages of the book flapping like brittle kindling, her face burning with the joy of chapter nine.

Tuesday, August 29, 2017

Prewriting isn't about organizing a bunch of nothing into paragraphs

Writing Suggestion: Get kids writing. Most people understand the concept of prewriting. Yet there is a distinction here worth noting. ...Prewriting is not always about creating a piece of prewriting for a specific text. The point is to generate prewriting that could turn into any text. The point is to create a place where kids can return when they are looking for substance and examples and facts and models and illustrations and quotes and so much more. Maybe we have 2's on STAAR because we haven't helped kids activate their funds of knowledge. Maybe we have 2's on STAAR because they are trying to organize a bunch of nothing into five paragraphs.

The beginning of the year is the perfect time to help kids understand that they have many things to say and plenty of feelings and experiences. These become seeds for generating ideas that they can use on many papers, not just one. This approach also honors the concept of choice. People will write more about things that they care about, are in the mood to think about, and know something about.

(NOTE: I learned about this sequence of instruction from Gayla Wiggins at Lead4Ward. It was just THE thing to bring together the other things I had been building and thinking. She’s a genius. It perfectly follows the gradual release of responsibility and balanced literacy models.)

- 5-7 Quickwrites - In the first six weeks, start with some Quickwrites. Which ones will you use?

- Something else?

- 4-5 Thinkwrites - Weave in some prewrites that involve thinking.

- Blueprinting - my favorite

- Something else?

- Let kids choose what they would like to write about. These become the anchor, or seed papers ,students use to experiment with the skills and strategies you are learning about in reading and writing lessons.

Be sure to let kids talk with each other about the ideas they have chosen.

- Start a collaborative draft. The basic idea here is to brainstorm some ideas and topics. Gayla gave us a choice of social issues. We formed groups and read texts on the ones we were interested in. After that, we discussed the issues with our group members. We jotted down our ideas and placed them in our group notebook. Now the group is set up to apply all the lessons as the teacher addresses them with whole group instruction.

- The teacher models how to brainstorm and plan for writing a paper.

- Then the group collaborates to complete the same task with their group.

- The groups all share their process and products, discussing their work and refining their thinking and products.

- Then students enter their individual papers to apply the same strategy.

- And so on through the writing process and specific TEKS for the unit.

Friday, August 25, 2017

Need a Vocabulary Program?

We

are on the hunt for great tutorial material to boost our students success with

Figure 19 and Vocabulary. Do you

know of a school that has a strong program that we might visit with?

When this question came in, I told my coworker that I felt a rant coming on. Here it is.

I am not a fan of "programs" and as a Region 16 employee, I'm not really supposed to be recommending any program over another. But, there are some ideas and principles that can structure an effective vocabulary approach.

This question, though, is exactly on point. Figure 19 and Vocabulary are intricately linked. Vocabulary, specifically the use of context clues, is a cognitive activity that we use to comprehend a text. Vocabulary, as context clues, is a metacognitive activity represented in our TEKS. Vocabulary is also a cumulative process of word knowledge:

3.4D playful uses of language: tongue twisters, palindromes, riddles

4.2D idioms

5.2D idioms, adages, and other sayings

6.2D foreign words and phrases commonly used in written English (RSVP, que sera sera)

7.2D foreign words and phrases commonly used in written English with an emphasis on Latin and Greek words and phrases (habeus corpus, e pluribus unum, bona fide, nemesis)

8.2D common words or word parts from other languages that are used in written English (phenomenon, charisma, chorus, passe, flora, fauna)

9.1D origins and meanings of words or phrases used frequently in English (caveat emptor, carte blanche, tete a tete, pas de deux, bon appetit, quid pro quo)

10.1D relationship between origins and meaning of foreign words or phrases used frequently in English and historical events or developments (glasnost, avant-garde, coup detat

11.1D cognates in different languages and of word origins to determine word meaning

12.1D how English has developed and been influenced by other languages

There is no list or sequence of words that can be found that will match what each grade level needs to know to be able to read. There is too much that has been written. There is too much left yet to be said. It is impossible to predict or dictate a certain number or precise selection of words each person will need.

Our approach, therefore, must have two prongs. Programs available in the market can't do both. Not a single one of them. And such a program is unlikely to ever be developed.

Prong One: Realize that context clues cannot be assessed the way we use them to comprehend. Teaching vocabulary in context with comprehension must be a part of reading instruction. That kind of teaching will never come from a list. There is not a particular sequence of steps or rules that will guarantee that people will understand what a word means. Sorry. There just isn't. When we tell our kids silly things like "use the words in the sentence to help you understand the word" and "look at the sentence before and after the word to help you know what it means" we are not teaching vocabulary or context clues. We we do that, we are teaching context clues as if they were some kind of textual seek and find on a Chili's children's menu. It's not that easy. We are not really teaching them how to mine the text to figure out what the words mean and how they are associated with the author's purpose, connotation, or craft.

Our mistake in teaching context clues is thinking that it is about words. It isn't about single words. And it's certainly not about circling the correct answer on a multiple choice item. Teaching about context is about how all of the text is food that delivers the nutrients of the author's message. Context clues are about how you digest something the author says that you can't quite chew or process, - that you don't understand. Sometimes, the author will use a word, or a phrase, or even a paragraph that you don't understand, but it doesn't really matter to understanding what the author says. You just let that pass or push it to the side of your reading plate.

But sometimes, the author will use a word that is critical to understanding what the author communicates. If you don't stop to chew, that chunk will choke your comprehension. Context clues are about deciding when you need to know what a word is and when you don't. Context clues are about how you use all of the text to help you figure that out.

Prong Two: We also need an explicit, sequenced focus on how we introduce and practice new words. That's called Word Study. We do that in several ways.

3. We select content words and cognates.

Don't waste your money on "vocabulary" programs:

Buy some books.

Read, discus, and write.

Repeat.

See also:

www.intensiveintervention.org/chart/instructional-intervention-tools

https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/

See also:

www.intensiveintervention.org/chart/instructional-intervention-tools

https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/

How Context Clues are Assessed on STAAR

During a recent meeting with Gayla Wiggins and Lead4Ward, Gayla said, "Context clues are not assessed the way they are used." It blew my mind. I met with a group of friends to tease apart the ideas. Essentially, we decided that we are teaching context clues as a skill rather than as a process.

Using context is a metacognitive process, not a set of steps you go through to find out what a word means. Telling kids to look in the sentence to find the clues won't always work. Telling kids to look at the sentences before and after the word is used won't always work either. As a matter of fact, "the chances of using a single context to derive a word's meaning are slim (only about 15 percent of the time) and doing so often requires and extensive amount of inference" (Trainer notes, Reading to Learn Academy, Vocabulary, slide 19). That shocked me.

But it does make sense. Nuanced text hardly ever gives a single piece of evidence. Yet nuanced text does give multiple pieces of overarching context if you use the whole text to make meaning. To use my favorite example, we can't teach kids to answer vocabulary questions as if it were a Seek and Find on a Chili's children's menu. If kids are reading the question, then going to the text to find the word, reading "around" the word, that's not context. That's isolation. No amount of circling or highlighting is going to help the child understand the word. Nuanced text won't have enough information to help the reader understand the meaning of the word. Besides, reading isn't about understanding one word. Reading is about how all the words coalesce to deliver the author's message. Context clues aren't about understanding the words. Context clues are about how you use the words to understand the point of the text. Understanding one word is not -and hopefully will never be -the point of authentic writing or reading.

The following examples come from the 8th Grade 2017 Released Reading STAAR Exam.

Here's an example. The question asks students to look for a word found in paragraph 2. The evidence listed in the multiple choice items is also from paragraph 2.

And here's another example. Just because the word is in paragraph 5 doesn't limit the evidence and context to paragraph five. Understanding the WHOLE passage brings the reader meaning about how the word is used and connected to what the author is saying with this word. In this case, a secret strategy for success.

Using context is a metacognitive process, not a set of steps you go through to find out what a word means. Telling kids to look in the sentence to find the clues won't always work. Telling kids to look at the sentences before and after the word is used won't always work either. As a matter of fact, "the chances of using a single context to derive a word's meaning are slim (only about 15 percent of the time) and doing so often requires and extensive amount of inference" (Trainer notes, Reading to Learn Academy, Vocabulary, slide 19). That shocked me.

But it does make sense. Nuanced text hardly ever gives a single piece of evidence. Yet nuanced text does give multiple pieces of overarching context if you use the whole text to make meaning. To use my favorite example, we can't teach kids to answer vocabulary questions as if it were a Seek and Find on a Chili's children's menu. If kids are reading the question, then going to the text to find the word, reading "around" the word, that's not context. That's isolation. No amount of circling or highlighting is going to help the child understand the word. Nuanced text won't have enough information to help the reader understand the meaning of the word. Besides, reading isn't about understanding one word. Reading is about how all the words coalesce to deliver the author's message. Context clues aren't about understanding the words. Context clues are about how you use the words to understand the point of the text. Understanding one word is not -and hopefully will never be -the point of authentic writing or reading.

The following examples come from the 8th Grade 2017 Released Reading STAAR Exam.

Here's an example. The question asks students to look for a word found in paragraph 2. The evidence listed in the multiple choice items is also from paragraph 2.

But look at how much evidence is peppered THROUGHOUT the text supports the meaning of that word. Reading the ENTIRE text is the context. Not one sentence. Not one paragraph. By teaching kids to only look at a portion of the text without consideration of the meaning of the whole text is a bizarre test taking strategy to handcuff kids to certain misconceptions about context clues as well as how we are really supposed to use context in actual life. Again, the focus of reading this passage is not to understand what scant means. It's about something more important.

And here's another example. Just because the word is in paragraph 5 doesn't limit the evidence and context to paragraph five. Understanding the WHOLE passage brings the reader meaning about how the word is used and connected to what the author is saying with this word. In this case, a secret strategy for success.

If I had the time, and thought you would read it, I'd record a think aloud about how each piece of highlighting helps me understand the words and the author's message. But, I don't have the time. And you probably didn't read all the way to the end anyway.

Fluency Applied to Writing: Handwriting and Typing

Part of the reading academies this summer addressed fluency. In our sessions, some of us started talking about the connection between fluency and handwriting. I started looking for some guidance and found some interesting research.

When kids compose, their handwriting and typing speed can inhibit their ability to transfer their ideas onto paper. Here are some important principles I learned:

- Find out how fast kids can copy information. There is a limit to how fast people can copy information. The fastest speed that they can copy information legibly should follow these rates:

- 1st - 5 words per minute

- 2nd - 6

- 3rd - 7

- 4th - 8

- 5th - 10

- 6th - 12

- 7th - 14

- 8th - 16 (Amundson, 1995).

- The faster you can copy, the more room you have in working memory to process thought. So kids who have trouble with automaticity and fluency in handwriting or typing can negatively impact the content of their writing.

- Kids in 4th grade typically compose using handwriting at 4-5 words per minute. By the time they are in the 9th grade, they compose using handwriting at 9 words per minute (Graham, 1990). Most adults compose at about 19 words per minute (Karat, Halverson, Horn, Karat ,1999).

- If kids can type at least 10 words per minute, that seems to match handwriting speed pretty closely. That means that if they type slower than that, typing actually makes it harder to compose. I think that should mean that kids should reach a benchmark in typing speed before being allowed the privilege of using the computer to compose. (Excluding assistive technology use.) If you can't type as fast as you write, you're going to be frustrated.

- Handwriting ability and keyboarding ability are NOT associated. In other words, if you have good handwriting it doesn't mean you can type well or not. BUT, kids should learn the basics of handwriting before learning to type. A concentrated focus on typing then, should probably begin after kids learn to write in cursive - my opinion.

- When composing, most adults who type can produce between 10 and 18 words per minute (Foulds, 1980). Most 5th and 6th graders who can type well usually compose at about 6 words per minute (Graham, Harris, MacArthur, and Schwartz, 1991). So 10 words per minute minimum seems like a good benchmark for deciding how fast kids should be able to type before begin asked to compose on the computer. Again, my opinion.

- Most research suggests that effective use of software requires a baseline of about 20 words per minute.

- Some suggest that typing speed should be 2 to 3 times faster than handwriting speed.

- Boys tend to type slower than girls, but almost catch up by 8th grade (Honaker, 2003).

- Most of the businesses that I looked at online require at least 30 words per minute. The ability to type 40 words per minute is considered an average typing speed. Professional typists have averages above 65 to 75 words per minute. Some people think most of the population doesn't have the finger dexterity to type above 50 words per minutes. So, looks like we should have kids typing between 30-40 words per minute by the 8th grade.

- The technology apps for 6, 7, and 8th grade don't mention a specific speed.

- The fastest anyone ever typed is 216 words per minute!

Link to Resource with charts

Link to Standards document that might be useful in curriculum development and integration of these ideas.

Review of Literature

Another review for handwriting speed

An assessment you can use

References:

Amundson, S.J. (1995). Evaluation tool of children's handwriting. Home, AL: O. T. Kids.

Foulds, R. A. (1980). Communication rates for nonspeech expression as a function of manual tasks and linguistic constraints. Proceedings of the International Conference on Rehabilitation Engineering. Toronto.

Graham, S. (1990). The role of production factors in learning disabled students' compositions. Journal of Educational Psychology. 82, 781-791.

Graham, S., Harris, R. K., MacArthur, C., & Schwartz, S. (1991). Writing and writing instruction for students with learning disabilities: Review of a research program. Learning Disability Quarterly. 14, 89-114.

Graham, S., Beringer, V., Weintraub, N., & Schafer, W. (1998). Development of handwriting speed and legibility in grade 1-9. Journal of Educational Research, 92(1), 42-52.

Karat, C., Halverson, C., Horn, D., Karat, J. (1990). Patterns of entry and correction in large vocabulary continuous speech recognition systems. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '99). New York, NY: ACM. pp. 568-575. doi: 10.1145/302979.303160.

Monday, August 21, 2017

Inference Hooey: Part III Addressing Process for Building a Mental Model

The second thing people do when they make inferences is building a mental model. Especially when they don't have one to begin with. And that's a real life skill, ya'all. I have to do stuff all the time that I know nothing about. Like learn how to turn on the dad gum television. Or build one of those boxes so I can look at the eclipse. But that's another set of stories.

Comprehension Purpose Questions:

To me, this implies two things: Either WE set a purpose for them. Or THEY set a purpose for THEMSELVES. Both are essential. Most sane people don't do things they don't have reasons for. Reading isn't any different. Setting a purpose before you read allows you to, well, have a purpose. In addition, it allows you to:- have a basis from which to examine the ideas,

- think actively,

- have a standard from which to monitor comprehension,

- and establish what content you must review to reach understanding (Center for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement, 2001; Collins-Block, Rodgers & Johnson, 2004; Coyne, Chard, Zipoli, & Ruby, 2007; Duke & Pearson, 2002; Dycha, 2012; Vaughn & Linan-Thompson, 2004).

Set by the Teacher: The reading academies suggested that teachers develop and pose Comprehension Purpose Questions (CPQ's) before students read. The example in the academy came from an article on the Shasta Dam. "How does the Shasta Dam help people in California?" and "How is the building of the Shasta Dam an example of humans overcoming nature?" were two good examples of CPQ's. "In what state is the Shasta Dam?" and "When was the Shasta Dam built? were non examples.

Set by the Student: The reading academy did not address a strategy for setting their own purposes for reading, but there are many resources for teaching students how to do this work.

Here are some ideas:

1. Anticipation Guides (Befre/After)

2. Say Something Chart (During)

3. SQP3R (Before, During, After)

4. List/Group/Label (Before)

5. Probable Passage (Before/After)

6. Coding Text (During)

Caution: Don't forget that the point here is NOT about the strategies or posing questions to interrogate the reader. The point here is that getting your mind right about what you are about to read is a process that you go through so that you can comprehend. It's a mental model that good readers use to be successful.

Types of Inferences: Kids also need to have a mental model about the types of inferences that might confront them as they make sense of text. Beers lines these out for us along with suggestions (2003). Perhaps modeling each of these instances would be a good starting place for mini-lessons.

- recognize the antecedents for pronouns

- figure out the meaning of unknown words from context clues

- figure out the grammatical function of an unknown word

- understand intonation of characters' words

- identify characters' beliefs, personalities, and motivations

- understand characters' relationships to one another

- provide details about the setting

- provide explanations for events or ideas that are presented in the text

- offer details for events or their own explanations of the events presented in the text

- understand the author's view of the world

- recognize the author's biases

- relate what is happening in the text to their own knowledge of the world

- offer conclusions from facts presented in the text (Beers, 2003, p. 65).

Use Text Structure:

Authors are purposeful in selecting text structures and genres that will most effectively convey their message and purpose and voice. This reminds me of learning how to play canasta. And most recently of teaching my grandson to play Old Maid. When grandma taught me to play canasta, we started playing with an open hand while I learned the rules. That way she could advise me about the choices evident from the cards in my hand. Text structure is how we learn to play the game with narrative and expository texts. What we have in our "hand" determines how we play the game. If you don't know the possibilities and strategies that structure the game, you probably aren't going to win. Or you can throw a fit and tip the game table like my grandson did when he drew the old maid from the deck. That too. I think sometimes that's what kids do, they just refuse to play/read because they think they can't win. Fortunately, the game doesn't have to be over when you draw the Old Maid.

In the TEA academies, their recommendations for narratives included: discussing the relationships among characters, setting, and events and linking relationships to the larger theme. Beers goes a bit further and suggests that we should have an anchor chart of the types of inferences and specifically name them as we model and discuss the connections.

Recommendations for informational tests included using specific structures commonly used and learning key words associated with each of these structures.

For both genre types, TEA suggested the use of graphic organizers. I don't think you need any help in finding those.

Caution: Again, let's be clear. The point is not to identify text structures, but to use them to help make inferences because the provide a mental model for the process we use as readers to make meaning.

Beers, K. (2003). When kids can't read: What teachers can do. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Collins-Block, C., Rodgers, L., & Johnson, R. (2004). Comprehension process instruction: Creating reading success in grades K-3. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Coyne, M. Chard, D., Zipoli, R. & Ruby, M. (2007). Effective strategies for teaching comprehension. In M. Coyne, E. Mame'enui, & D. Carnine (Eds.) Effective strategies that accommodate diverse learners (pp. 80-109). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Duke, N. K. & Pearson, P. D. (2002). Effective practices for developing reading comprehension. In A Farstrup and S. Samuels (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction. (pp. 205-242). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Dycha, D. (2012). Comprehension, Grades K-3. In M. Hougen & S. Smartt (Eds.), Fundamentals of literacy instruction and assessment, Pre-K-6. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Vaughn, S., & Linan-Thompson, S. (2004). Research-based methods of reading instruction: Grades K-3. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

STAAR Scoring for Writing: Conversation with TEA

I just got off the phone with TEA. I have tried to replicate what I learned with fidelity to TEA's message; however, I realize that there are probably ways that I state my understanding that TEA would NOT officially endorse.

(For background understanding of why I called TEA: I have been getting a

lot of questions about how the essays were scored, what we can do to improve

scores, and the possibility of offering a scoring training.)

- TEA

is aware of inconsistencies in scoring and are addressing them as well as

they can with the “constructs of the contract.” There is a rescoring

policy in place if you feel there are papers that need to be reconsidered.

- They

HAVE NOT changed their tenets to value formulaic writing. TEA’s advice about authentic products is still in place.

- Paragraphing is great in the real world. Real world writing is

not constrained by genre or 26 lines. They do NOT look at paragraphing AT

ALL for STAAR.

- The

biggest problems are with essays that try to follow these patterns:

- 4

paragraph essays with no ideas fully developed; they repeat or say

nothing. There’s not enough room in 26 lines for 4 paragraphs.

- 3

paragraph essays with two body paragraphs that contain examples. The examples

don’t say much. (In other words, the ideas are not developed.)

- Perfunctory

transitions like first, next, finally do nothing for the paper. Transitions should link the ideas between paragraphs and connect back to the thesis.

- Kids

are not planning or prewriting in their booklets. Only about 30 percent

are doing anything at all. And most of those just start writing and then

recopy what they wrote onto the answer document.

- TEA

recommends that we focus more on the PLANNING element of prewriting.

- TEA

recommends that we help kids have the courage

to cross out stuff/delete information that does not go directly with the

thesis. (I thought that was a nice way to say that.)

- Kids

are still getting stuck in the box/stimulus. The 4th graders last year really had a problem with that. (We need to help them find

the prompt – the writing charge.)

- Biggest

problems between 1’s and 2’s were: no thesis and weak conventions

- Biggest

problems between 2’s and 3’s was development of ideas and organization.

Kids who used anecdotes included too much information that didn’t connect

back to the thesis. There was too much repetition.

- Biggest

problems between 3’s and 4’s was still development of ideas and

organization. Kids who could use historical information and cultural facts

accurately seemed to do the best. Using knowledge from other disciplines

seemed to work well. Organizational structures really pushed the papers up

to a 4. They try to include these examples in the scoring guides. (I would

add that this is not demonstrate causality. Writing about history or

culture is not going to get you a 4. It’s just that kids who are doing

better in writing have more knowledge and schema to draw from.)

- There

is always a lot of talk about addressing the prompt. TEA is responsive to

kids and allows the kids to approach the prompt however they choose. For example,

the fourth grade essay about meeting someone they have never met? They

allowed kids to write about fictional characters, JJ Watt, and even allowed

a kid to write about meeting a grandmother for lunch as long as they talked about that person AND why they wanted to

meet them.

- There

is a technical digest published that gives us guidance on how raters are

trained. Look at this link, starting on page 16: http://tea.texas.gov/Student_Testing_and_Accountability/Testing/Student_Assessment_Overview/Technical_Digest_2015-2016 The new one for last year should be published in February.

- They

use the scoring guides as the anchor papers for the training sets. We don’t

have those for last year’s testing yet, but we have them for previous years.

- They

were going to provide us with an

online training guide that ETS uses for training raters. Because of the

changes in TEA organization and budget, this probably will NOT be released.

- The

new organizational structure will take place after September 1st.

There will no longer be a distinct division between Content folks and

Assessment folks. Staff will be working on BOTH content and assessment.

Scheduling Components for the ELAR Classroom

When I attended the Lead4Ward ELAR Academy recently, I posted a picture about my learning about how to schedule all of the components into a 45 minute classroom. This is a terrible struggle for many teachers, and certainly one of the most frequently asked questions when I lead staff development. "How do I fit it all in?"

Gayla Wiggins recommended 2 components per week. She said that we need to also be flexible because we are a "responsive" discipline.

Here are some more of my notes based on her recommendations:

1. It might feel disjointed at first. You will have a problem with the "flow" at first, but you need to know that it is ok to shift from one thing to another.

2. The key is balance in getting in all the things that students need.

3. It's easier to plan with a theme, but you don't have to. Be sure to get LOTS OF TEXTS into their reading. Be careful when you are planning that you don't become so focused in finding stuff that matches your theme that you forget the WHY behind your choice. The purpose is to teach kids the reading and writing processes they will need for success.

4. Shared reading time gets shorter throughout the year and more and more time is reserved for independent reading.

5. Notice the balance of time between reading and writing.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)